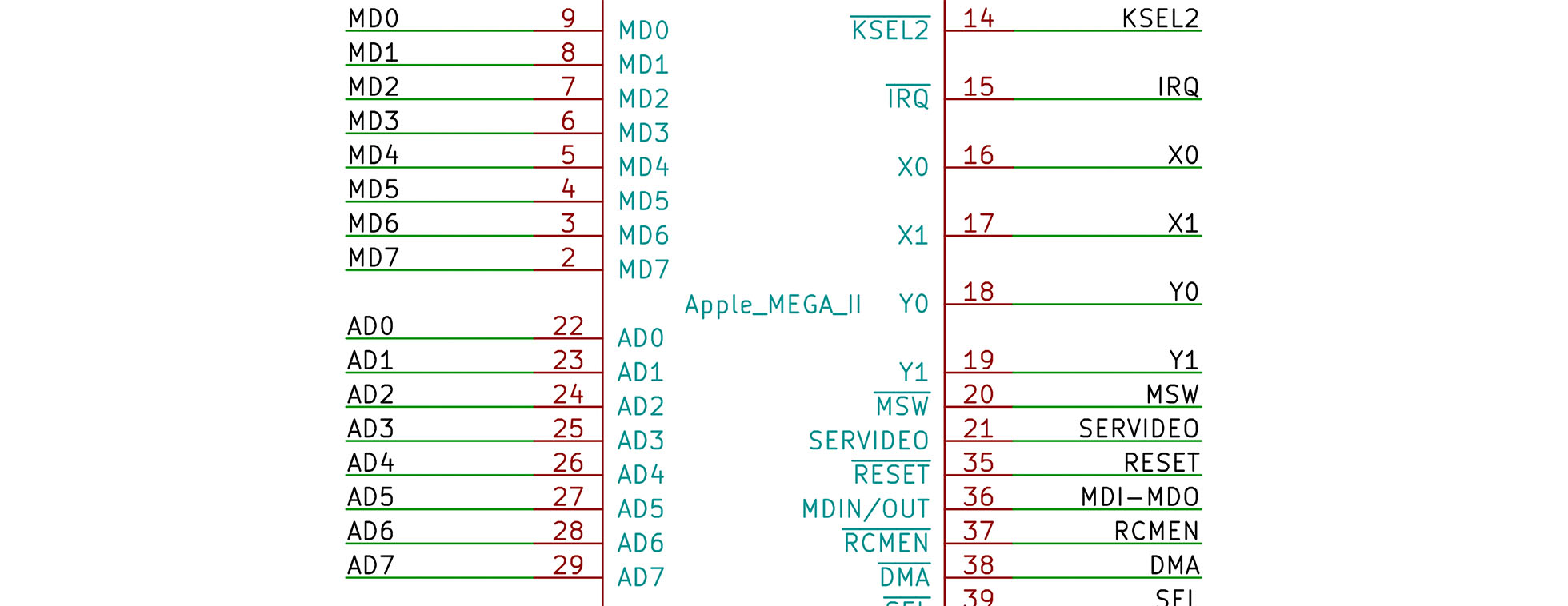

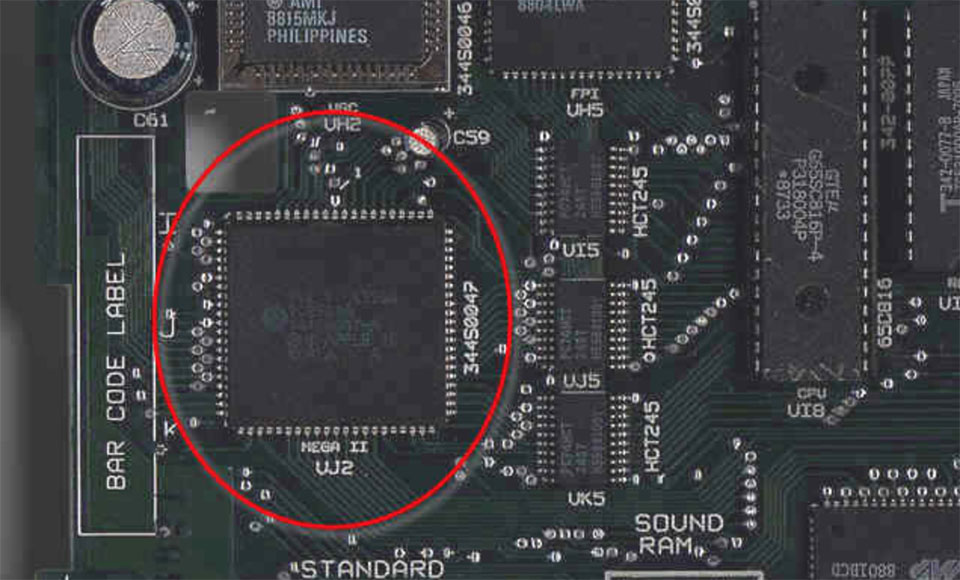

A project I work on in my spare time is creating a portable Apple II. Like many of my projects, one leads into another. I started out wanting to make a mobile Apple II, and now I’m working on a project called Bit Preserve. How did I get from one project to the next? Well, as I looked into how to make a portable Apple II, I realized a significant issue. The original Apple II logic board has almost 80 ICs. Being a design from 1975, they are all through-hole packages. The good news is that except for the ROM chips, they are all off-the-shelf components. But such a size means it might be impossible to turn it into something handheld. I almost abandoned the project. Then, I learned about a chip included in the Apple IIgs. The name of the ASIC is “MEGA II.” (Nothing to do with Arduino.) It is a chip that integrates all of those off-the-shelf chips into an 84 pin package.

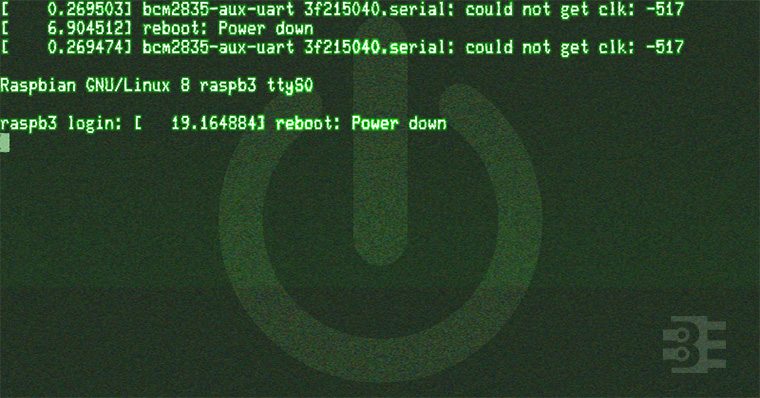

As I dove deeper into the project, I realized I needed other support chips to make the MEGA II useful. There is a decent book that discusses the technical details of the Apple IIgs, but it does not get into chip or board level design. For that detail, I had to look at the original schematics. While I am ecstatic that someone archived these original documents as PDFs, I quickly became frustrated. Sometimes the scan quality is not very good, and it is nearly impossible to search for symbols across multiple pages. I thought to myself, “There has got to be a better way!”

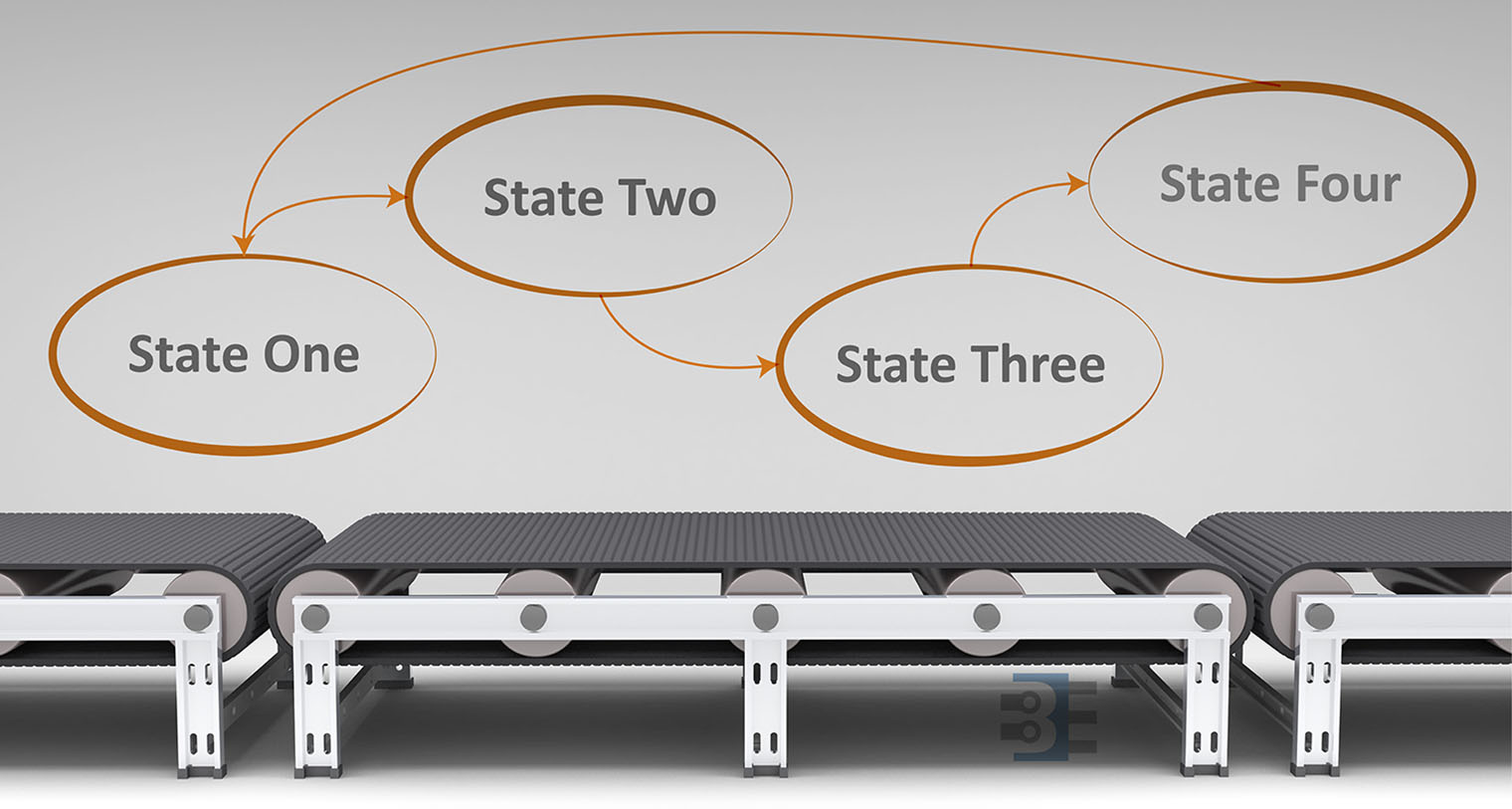

Bit Preserve on GitHub